Aren't they too young?

We often hear these questions about multicultural education for young children:

“Aren’t children too young for critical multicultural education?”

“Isn’t early childhood a time for play and innocence?”

“Will learning about injustice frighten or traumatize young children?”

“Aren’t they too young to understand?”

“Aren’t children too young for critical multicultural education?”

“Isn’t early childhood a time for play and innocence?”

“Will learning about injustice frighten or traumatize young children?”

“Aren’t they too young to understand?”

When you hear the word childhood, what images come to mind? Who and what do you see?

Study the images below. How are they* similar or different from what you imagine? What factors affect these difference or similarities? Personal experience? Media? Social Media? Entertainment shows?

When we think about childhood and young children, we need to recognize that childhood is a socially and culturally constructed concept that has changed over time. Not all children experience childhood in the same way and the construct of childhood is often contested. As educators, we need to recognize our own positionality and its implications for how we teach. We may wonder whether young children are developmentally ready for multicultural education, yet few would argue with the idea that best early education programs are child-centered.

Let us start with NAME’s definition of Multicultural Education:

Multicultural education advocates the belief that students and their life histories and experiences should be placed at the center of the teaching and learning process and that pedagogy should occur in a context that is familiar to students and that addresses multiple ways of thinking.

If our objective is to support all children’s development to their potentials, it is essential to design curriculum and pedagogy in ways that build on each child’s prior cognitive, socio-emotional and cultural and linguistic learnings and resources. Developmentally Appropriate Practice (DAP) dominating the narrative around early childhood education is grounded in psychological models that may ignore the very contexts that support child-centered pedagogy. A “colorblind” approach to early education may make diverse students’ strengths, knowledge and abilities invisible. Multicultural Education is a mandate if we are to provide equitable educational opportunity for all students.

Approaches that recognize and nurture diversity build towards the NAME Multicultural Education Outcome:

Positive social identities

Positive social identitiesBelow, we discuss several aspects of engaging young children in critical multicultural education, including developmental readiness, types of curriculum, educator concerns and the necessity to approach such conversations despite their difficulty or a sense of being uncomfortable in engaging the discussion.

Are young children aware of differences between people?

Yes, young children are aware of differences. Young children are deep thinkers. During the early childhood years, children are developing their own identities, their attitudes toward others, and awareness of differences of all kinds, including but not limited to race, gender, culture, religion, and language. Take a look at this video clip from “Skin Color: The Way Kids See It” to see how young children express attitudes towards differences in skin color. The video shows young children who are aware of skin color differences and also of the positive and negative value judgments attached to them. These value judgments are shaped by dominant cultural norms.

Respectful engagement with diverse people

Respectful engagement with diverse people

Isn’t early childhood a time for play and innocence?

For young children, play is a time to test and explore the complexity of their world. Consequently, play is a place where educators can listen, observe and engage children in themes related to multicultural education. Nancy Pelo (2008) writes:Social justice teaching grows from children's urgent concerns. If we listen to the themes embedded in children’s play and conversations, we hear questions about identity and belonging, about community and relationships and fairness…And, in their everyday negotiations, children are working to make sense of the ways in which people are the same and different… Children are fundamentally concerned with making sense of their social and cultural world; teachers and caregivers can join them in this pursuit, guiding them towards understandings. (pages xi-xii)

In teaching, what are your main fears related to multicultural and anti-racist teaching? Be honest and identify, out loud, what concerns do you feel you have in engaging children in teaching about diversity, equity and inequity. Do you worry that the children might develop fears or nightmares, or that children might feel guilty or responsible for suffering?

Children are aware of the world around them, and perceive the affective climate of issues and problems even if adults do not explicitly speak to them about issues and even if adults explicitly attempt to hide issues and problems. Children may be confused if there is no support from adults who are their caregivers to help them understand the difficult and complex world in which they live. Addressing questions of fairness and equity with young children, using words and activities they can understand, and in communication with and inclusive of their families and communities, moves towards the NAME Multicultural Education Outcome:

Social justice consciousness

Social justice consciousnessWhat does multicultural education for young children look like?

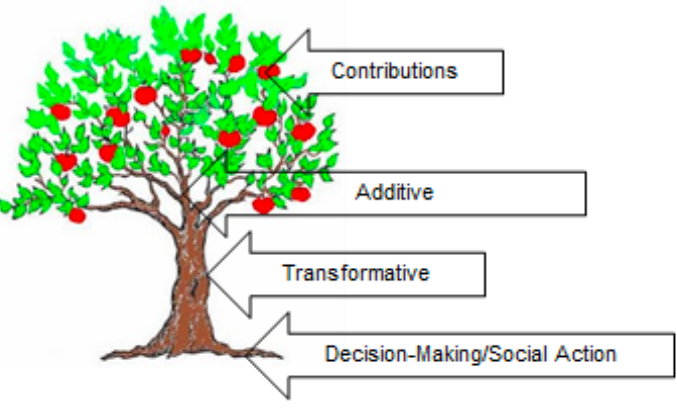

Sound multicultural education practices start with understanding and honoring children and their families. Deeper levels of multicultural education explore changing fundamental ways of teaching and interacting in our classrooms and engage children towards equity and social justice. Here Banks’ (1988) multicultural education framework is presented through the image of a fruit-bearing tree:

Recognition and normalization of surface differences, like the way people eat, is a positive step, but it is not enough for a critical multicultural education. Understanding of cultural difference and questions of equity must move teachers to reshape curriculum and pedagogy in deeper ways.

In the second approach, the Additive approach (branches), teachers begin to “branch out” of the mainstream curriculum and teach events or a group’s experience that are missing from the mainstream norm. For example, a teacher might create a thematic unit about differently-abled children. Play materials might include non-traditional gender-role dolls or action figures.

The Transformative approach is the trunk of the tree because it is foundational to how lessons are taught and learned. A Transformative approach, in contrast to Contributions and Additive, entails a fundamental shift of perspective, recognizing that norms are shaped by social, cultural, and political views about gender, language, ability, citizenship status, religion and other aspects of identity. A Transformative approach is reflected in the many decisions teachers make every day and consistently over time about the perspectives through which lessons, activities and conversations are framed. Teachers must make special efforts to situate diversity as the norm throughout the curriculum and pedagogy. This might mean deliberately acknowledging a variety of examples of families and family structures in everyday language with children rather than always referencing a mother and father. It might mean demonstrating that it is normal and valuable to speak languages other than English. With the Transformative approach, teachers need to rethink their own attitudes and expectations around ways of learning, communicating and interacting, making room for multicultural pedagogy that builds on diverse strengths and perspectives of children and families.

The fourth of Banks’ approaches is rooted in Decision-making and Social Action. A healthy tree, like a healthy curriculum, is determined by the health of its roots. In this approach, adults support and guide children to develop their understanding of fairness and justice and become active participants in shaping the conditions of their world in the classroom and beyond. The video below, “No fighting in school.” shows teacher Marc Miller discussing the issue his kindergarten class addressed using a Problem-Solution Project (Stenhouse, Jarrett, Fernandes, & Chilungu, 2014). PSPs combine service-learning and critical pedagogy, building curriculum around a student-generated, student-centered process supported and facilitated by a teacher.

When children have agency to solve real problems, as Marc Miller’s students did, they move towards the NAME Outcome:

Social justice action

Social justice action

Banks’ four approaches are not static; they are meant to be organically interwoven as teachers develop multicultural curriculum and culturally responsive pedagogy. This means starting early with children to bring attention to and talk through their biases and worldviews. According to Louise Derman-Sparks (as cited in Pelo),

Banks’ four approaches are not static; they are meant to be organically interwoven as teachers develop multicultural curriculum and culturally responsive pedagogy. This means starting early with children to bring attention to and talk through their biases and worldviews. According to Louise Derman-Sparks (as cited in Pelo),

If children are to grow up with the attitudes, knowledge, and skills necessary for effective living in a complex, diverse world, early childhood programs must actively challenge the impact of bias on children’s development. (p. 9)

Educators often shy away from more critical and social justice aspects of a multicultural education, particularly with younger children. In her book, Black Ants and Buddhists (winner of the 2008 NAME Phillip Chinn ME Book Award, Mary Cowhey (2006) shares:

I chose to teach critically because I believe young children are capable of amazing things, far more than is usually expected of them. I am not talking about raising a score on a standardized math test (although that often happens.). I am talking about thinking critically and learning to learn, learning to use basic skills like reading, writing, solving mathematical problems, analyzing data, public speaking, scientific observations, and inquiry as an active citizen in your community. (p. 18).

Mary’s Thanksgiving lesson addresses issues of homelessness, equity and poverty with first grade students.

What about young children who speak languages other than English at home?

Children from any language background benefit by participation in a critical multicultural education early childhood program. Multicultural preschool programs must be aware of the integral relationship of language and culture. Children’s home languages and cultures are integral to children’s identities and to their cognitive, linguistic and socio-emotional development. An education program that aims to support the child’s learning must recognize, honor and nurture the home language and culture. Research on academic achievement shows that best long-term academic outcomes for Dual Language Learners are obtained when the home language is most strongly supported. (Espinosa, L. 2010) This short video offers a glimpse into the research-based SEAL bilingual early childhood program, providing an example of how diverse children's cultural and linguistic resources are valued and serve as the foundation for child-centered learning.

Isn’t it more important to focus on academic preparation and school readiness during preschool years?

Teaching is not neutral. If our goal is to nurture each child’s cognitive, academic. linguistic, and socio-emotional development, our responsibility is to recognize and nurture diversity, to guide each child’s growing understandings and interactions, and to create a learning environment that is inclusive of diverse families and communities. It may seem that academic pressures don’t leave time for “frills” like multicultural studies, but, if we don’t want to replicate societal inequities, multicultural education is not a frill! “In a culturally inclusive environment, teachers treat all students equitably, their languages and cultures are incorporated into the curriculum, and they are supported in becoming active seekers and producers of knowledge.” (Olsen, L. 2006) A key part of school readiness is the emergence of agency as a learner that leads NAME Multicultural Education Outcome:

Positive academic identities

Positive academic identitiesWhy is multicultural education in early childhood an imperative?

Sometimes adults confuse children because of their own discomfort in having conversation about “difference.” The mom interviewed in this video clip says “we never talked a lot about race,” surprised at the evidence of her daughter’s definite, strongly expressed attitudes.

Children observe their environments closely and mixed signals from adults may reinforce societal biases, prejudices, and stereotypes. Adults need to identify, and overcome their own fears and prejudices regarding these natural conversations. As parents/guardians and teachers wonder whether they should adopt a critical multicultural education approach with young children, they should consider the following:

- Children notice and make meaning of differences often internalizing or mirroring social and cultural responses to difference.

- Children learn just as much or more from what is unsaid as what is said.

- Children’s developing thoughts, values and beliefs are highly influenced by what and how a teacher teaches. A teacher’s thoughts, perspectives, values, and beliefs shape curriculum and pedagogy.

- Multicultural Educators build on students’ questions and observations as sources of curriculum development that leads to critical thinking, knowledge production, and socioemotional growth.

*Pictures from:

- Boy with gun in store

- http://parenteffectivenesstraining.net.au/children-playing-whats-the-big-deal/

- https://www.emaze.com/@AQCOLZWO/Untitled

- http://medialib.aafp.org/content/dam/AAFP/images/ann/2014-May/ROAR_Dad%20reading%20to%20children.jpg.daijpg.380.jpg

- Washington, D.C. Saturday 12/13/14: NATIONAL MARCH AGAINST POLICE VIOLENCE

- https://idealisticrebel.com/tag/child-soldier/

References

Banks, J. A. (1988). Approaches to multicultural curriculum reform. Multicultural Leader, 1(2), 3–5.

Bronson, P., & Merryman, A. (2009). Nurture shock. New York: Twelve Publishing.

Castro, D,, Ayankoya, B., & Kaszrpak, C. (2006). The New Voices, Nuevas Voces: Guide to Cultural and Linguistic Diversity in Early Childhood. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing.

CNN. “Kids Test Answers on Race Bring Mother to Tears.

CNN. “Skin Color-The Way Kids See It.” Posted to YouTube by CNN, 2010.

Cowhey, M. (2006). Black Ants and Buddhists. Portland, ME., Stenhouse.

Espinosa, L. (2010). Getting it RIGHT for young children from diverse backgrounds: Applying research to improve practice with a focus on dual language learners (1st edition). New York: Pearson.

Miller, M. “No Fighting in School”- A Problem-Solution Project. (See Stenhouse, et al., below.)

Olsen, L. (2006). Ensuring Academic Success for English Learners. University of California, Linguistic Minority Research Institute UCLMRI. 15 (4).

Pelo, A. (Ed.). (2008). Rethinking Early Childhood Education. Milwaukee, WI.: Rethinking Schools.

Sobrato Family Foundation. SEAL: An Introduction (2014)

Stenhouse, V L, Jarrett, O. S., Fernandes Williams, R. M., and Chilungu, E. N. (2014). In the service of learning and empowerment: Service-learning, critical pedagogy, and the problem-solution project. Charlotte, NC.: Information Age Publishing.

York, S. (2003). Roots and Wings: Affirming Culture in Early Childhood Programs ( Revised Edition). St. Paul, MN: Redleaf Press.